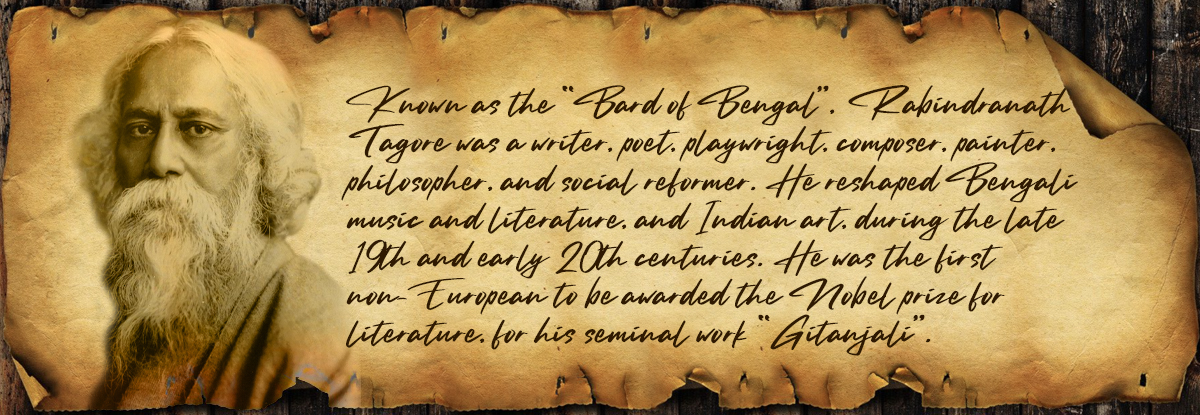

RABINDRANATH TAGORE

KNOWN AS THE “BARD OF BENGAL”, RABINDRANATH TAGORE WAS A WRITER, POET, PLAYWRIGHT, COMPOSER, PAINTER, PHILOSOPHER, AND SOCIAL REFORMER. HE RESHAPED BENGALI MUSIC AND LITERATURE, AND INDIAN ART, DURING THE LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES. HE WAS THE FIRST NON-EUROPEAN TO BE AWARDED THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE, FOR HIS SEMINAL WORK “GITANJALI”.

The Calcutta where I was born was an altogether old-world place. Hackney carriages lumbered about the city, raising clouds of dust and the whips fell on the backs of skinny horses whose bones showed plainly below their hide. There were no trams then, no buses, no motors. Business was not the breathless rush that it is now and the days went by in leisurely fashion.

Clerks would take a good pull at the hookah before starting for office, and chew their betel as they went along. Some rode in palanquins, others joined in groups of four or five to hire a carriage in common, which was known as a “share-carriage”. Wealthy men had monograms painted on their carriages, and a leather hood over the rear portion, like a half-drawn veil. The coachman sat on the box with his turban stylishly tilted to one side, and two grooms rode behind, girdles of yaksʼ tails round their waists, startling the pedestrians from their path with shouts of “Hey-yo!”

Women used to go about in the stifling darkness of closed palanquins; they shrank from the idea of riding in carriages, and even to use an umbrella in sun or rain was considered unwomanly. Any woman who was so bold as to wear the new-fangled bodice, or shoes on her feet, was scornfully nicknamed “memsahib”, that is to say, one who had cast off all sense or propriety or shame. If any woman unexpectedly encountered a strange man, one outside her family circle, her veil would promptly descend to the very tip of her nose, and she would at once turn her back on him.

The palanquins in which women went out were shut as closely as their apartments in the house. An additional covering, a kind of thick tilt, completely enveloped the palanquin of rich manʼs daughters and daughters-in-law, so that it looked like a moving tomb. By its side went the durwan carrying his brass-bound stick. His work was to sit in the entrance and watch the house, to tend his beard, safely to conduct the money to the bank and the women to their relatives’ houses, and on festival days to dip the lady of the house into the Ganges, closed palanquin and all.

Excerpts from ʻMy Boyhood Daysʼ by Rabindranath Tagore